Letter from Helsinki: Dream Archipelago

Reading time: 13 minutes

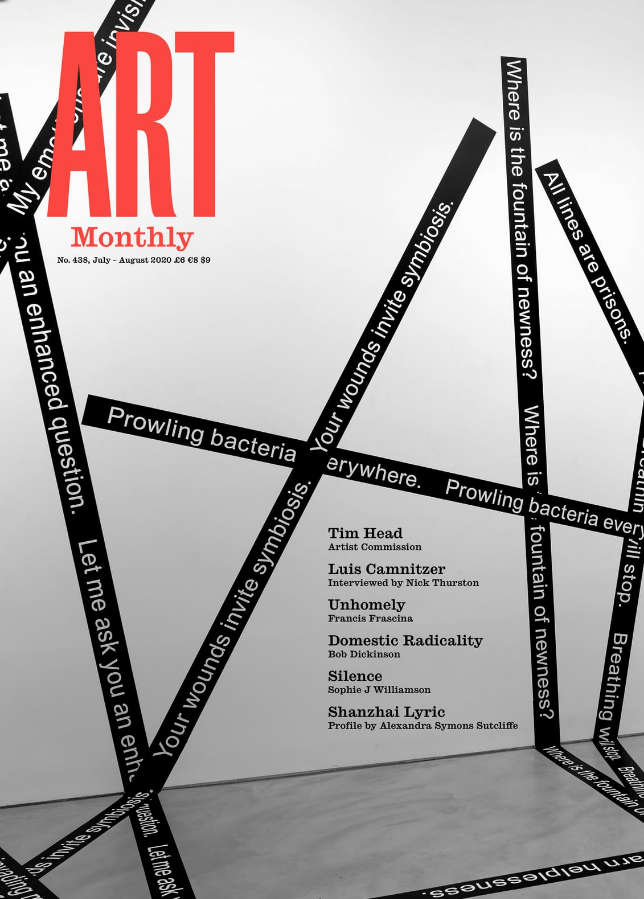

FIRST PUBLISHED IN ART MONTHLY, ISSUE 438, JULY-AUGUST 2020

They start to squeak after 9pm, small winged bodies, upside down, inching out from roosts in outbuildings and tree hollows. Their thick fur is yellow-tipped, giving them a tousled, golden appearance. The forest is an ideal hunting ground to catch insects in mid-flight. In the long days of the short Finnish summer, they give birth; their babies hunt independently in just three weeks.

The Northern Bat (Eptesicus nilssonii) is found across Central and Eastern Europe, the Artic Circle and here, in Finland, on Vallisaari Island of the southern Helsinki archipelago. The capital pokes out into the clean, cold waters of the Gulf of Finland, fed by the Baltic Sea, and is surrounded by 330 rocky islands. Due to host the inaugural Helsinki Biennial at the time of press, Covid-19 has forced this big event, like many others, to be pushed back twelve months, and production has ceased. The island itself can still be accessed by boat in around 15 to 20 minutes from Market Square. Hidden from view behind the more famous island of Suomenlinna, and separated only by a narrow channel, Vallisaari has been open to the public since May 2016; visitors can hop across <deleted> with a €12 JT-Line water-bus ticket.

Since the Middle Ages, Vallisaari (‘Embankment Island’) has provided drinking water and sanctuary for fishermen, pilots and smugglers alike. In the early 19th century, the Russians used the unguarded island to bombard Sweden’s sprawling sea fortress on Suomenlinna, eventually taking Finland from Swedish to Russian rule; it continued as a military base through both world wars, and its grounds are veined with underground bunkers to this day. More than 300 people lived here in the mid 20th century, farming small plots, until they dwindled in number. The last person left in 1996. The Finnish Defence Forces relinquished control in 2008, and it is now managed by Metsähallitus, Parks & Wildlife Finland.

What makes Vallisaari so special is its biodiversity. It is just a stone’s throw from the Finnish capital yet nature has been allowed to flourish for more than 20 years. It now boasts the richest environment of the 200 surveyed islands. Rich woodlands of aspen and bird cherry trees provide a habitat for around a thousand species of butterfly and moth, including the Plumed Prominent (Ptilophora plumigera), a tawny moth with extraordinary feathered antennae; the large, tufty-eared Eagle-owl (Bubo bubo) nests in fortifications along with around 60 other bird types; as well as several protected bat species, like our Northern friend, plus the Whiskered (Myotis mystacinus) and Grey Long-Eared bats (Plecotus auritus). It’s a ‘highly sensitive’ setting, say Finland’s National Parks, especially when put into wider context; the Ministry of the Environment has recently reported a ‘decline and deterioration of natural habitat’ that threatens every ninth species across the country.

And so 80% of Vallisaari is protected; it is a key part of the City of Helsinki’s Maritime Strategy, say Helsinki Biennial curators Pirkko Siitari and Taru Tappola. ‘Everybody has a right to use these locations,’ says Siitari – with a respect for its delicate ecosystem. The Biennial’s title, ‘The Same Sea’, draws inspiration from biologist and activist Barry Commoner’s first law of ecology, that ‘everything is connected to everything else’: oceans, seas, rivers, plants, animals, insects, humans, bacteria – viruses – all are, say Siitari and Tappola, part of ‘intertwined ecosystems that form actual and symbolic networks’. ‘I think that being in physical contact with nature has become more and more important during lockdown, and when all the connections have been virtual,’ says Tappola. ‘People are very hungry for tangible things. This Biennial connects nature and art, and the experience on the island will enforce these feelings, not only as an idea, but as a concrete thing.’

‘It’s interesting how coronavirus is making us aware of our human relations to other species,’ Siitari adds. ‘I’m happy if it will increase their awareness of how important nature is for wellbeing, and the urgency to protect our nature from issues of climate change.’

Helsinki Biennial will take place on the 20% of the island that is already open to the public. Even so, the practical aspects of operating on a site of historical and natural importance are varied and complicated, says Tappola. ‘Every move we make, plan, cable, everything, indoors or outdoors, has to be approved’ – by biologists and the forestry commission, who make sure that flora and fauna are not disturbed, and by the City, to make it safe and navigable for humans, who will be encouraged to use one route, entering Vallisaari at one harbour and leaving from another.

Siitari and Tappola are permanent curators at Helsinki Art Museum (HAM), which has been tasked by the city to run this first festival of contemporary art. Production was due to start one week before lockdown. The good news is that all the artworks and artists remain confirmed, and labour should start up again exactly as planned in time for a 12 June 2021 launch. Aside from the expected loss of visitor admission fees, HAM is totally funded by the city, so hasn’t yet felt the financial impact of the lockdown that other cultural organisations have (the €4m needed for the Biennial’s first two years has already been raised, through the city and the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation). Instead of being furloughed, HAM director Maija Tanninen-Mattila says, staff have been making condition reports on 500 outdoor sculptures in parks and neighbourhoods, assisting the Helsinki Aid helpline and food delivery service for the elderly, and otherwise working from home.

HAM, Kiasma and other national and municipal museums reopened at the beginning of June, as did commercial galleries, and have been coping in different ways; Galleria Heino has spent the extended break renovating, while Helsinki Contemporary has been trialling exhibitions viewed virtually in 360°. HAM’s new exhibition is a preparation of sorts for the biennial; a three-part video installation by visual artist Terike Haapoja and playwright Laura Gustafsson, Gustafsson&Haapoja: Museum of Becoming imagines society from a – fittingly – non-anthropocentric position.

Waiting for restrictions to ease, Tanninen-Mattila has been walking HAM’s empty galleries, contemplating how the visitor experience will physically change now and during the Biennial; with extended exhibition times, more hand washing and alternative formats. ‘It’s really hard to make any scenarios’, she says, ‘because we really don’t know whether there will be another wave of coronavirus – will we have to shut down again? It’s like reading tea leaves. But there are things we can do.’ Taking a ‘digital leap’ during the past two months, HAM took advantage of the city’s TV studios to document artists’ talks, streamed guided tours of the collections, and created video tutorials for home-schoolers. ‘We were already thinking of this,’ says Tanninen-Mattila, ‘but coronavirus just gave us a big kick up the behind. It’s been a good thing that we have been forced to think about it. The most important thing now is not to stop, rather continue and build up.’

One of a stipulated 50% Finnish line-up, Helsinki Biennial exhibitor Teemu Lehmusruusu believes that artists can never expect certainty in advance; that said, he is pleased that the delay of the festival, and the lockdown more generally, has afforded him time to test out ideas in the field – literally. Lehmusruusu’s work blends sculpture, gardening, electronics and biology, and recently he has been renovating a ‘land art farm’, as he calls it, with research colleagues and his young family; a sort of outdoor studio-cum-‘mental space’ two hours outside of Helsinki. He plans a site-specific proposal for Vallisaari called House of Polypores: a deconstructed, solar-powered organ, whose pipes will be made from ‘mycotecture’, a method of using polypores, or fungus, to create architectural forms. Emerging from the island’s military ruins, the organ will convert noises from the decomposing forest floor into music that will play into the open air, as if the island itself has composed a fantasy score. ‘It will last the summer season,’ says Lehmusruusu, ‘but is still organic matter; a bird can destroy a mushroom brick, or something unexpected can happen with extreme weather.’

By celebrating the diversity and decay of wild forests, the artwork circuitously critiques the way Finland uses ‘clearfelling-based’ woodlands management methods. The artist estimates that 5-10% of Finnish forests are left truly wild, and the rest are maintained for toilet paper and timber. ‘It’s not all bad; you are doing it in such a way that there is still habitat and a value for people. But we worry about losing the rest of these landscapes, and it’s a rising topic in Finland. When you go to an old forest, you feel in your body this diversity, a bodily, weird feeling. The economic forests are quite boring – not like this fairy-tale here on Vallisaari.’ The Finnish government is concerned, too; the aforementioned report acknowledges that conservation alone cannot ensure the protection of species, and biodiversity must be restored in ‘all use of natural resources and areas.’

Visitors will have to wait to hear Lehmusruusu’s interpretation of the archipelago’s whispers. But the island offers its own ancient, exceptional and, let’s not forget, incredibly fragile charms. ‘My first impressions were, “OK, there haven’t been people here for a while!”’, he remembers. ‘There is a nostalgic mood to it, but at the same time it’s very science fiction, as people are no more entering this nature-state. And there, you can see the city on the horizon; it feels like you are entering another realm.’

© Laura Robertson, 2020. Full text

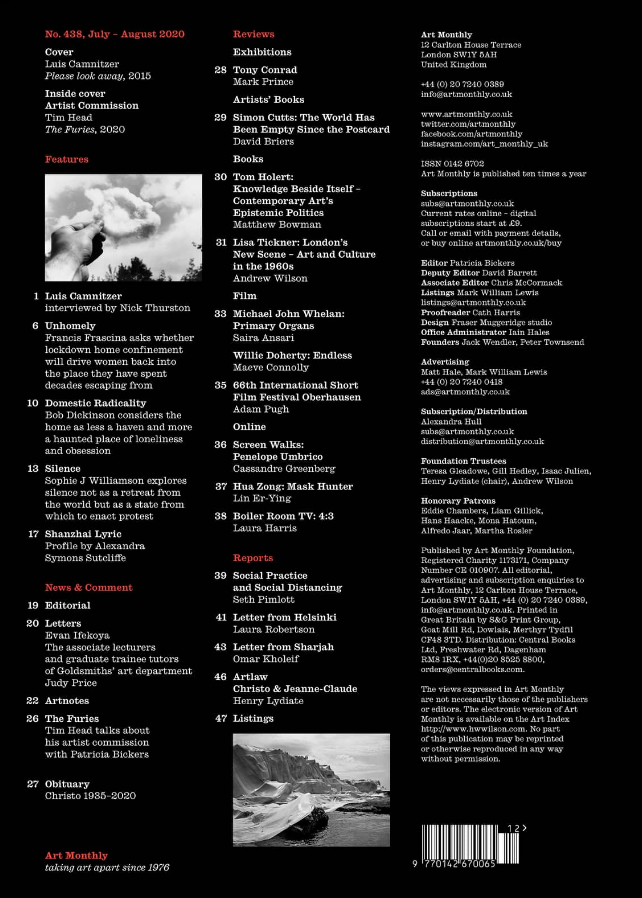

Image credits from top: Valisaari Island, Helsinki Biennial 2021: The Same Sea, 12 June – 26 September 2021, helsinkibiennial.fi

Teemu Lehmusruusu, installation view from Maatuu uinuu henkii (Respiration Field), Kaisaniemi Botanic Garden, Helsinki, 2019. Photo: Telling Tree art+rsrch

ART MONTHLY, ISSUE 438, JULY-AUGUST 2020